My interview for the "Volcanoes of the world" blog

Below is the translation of the interview I gave for the Polish blog wulkanyswiata. I hope it will be useful for the general public!

Where is the submarine volcano Kolumbo located, and what are its characteristics?

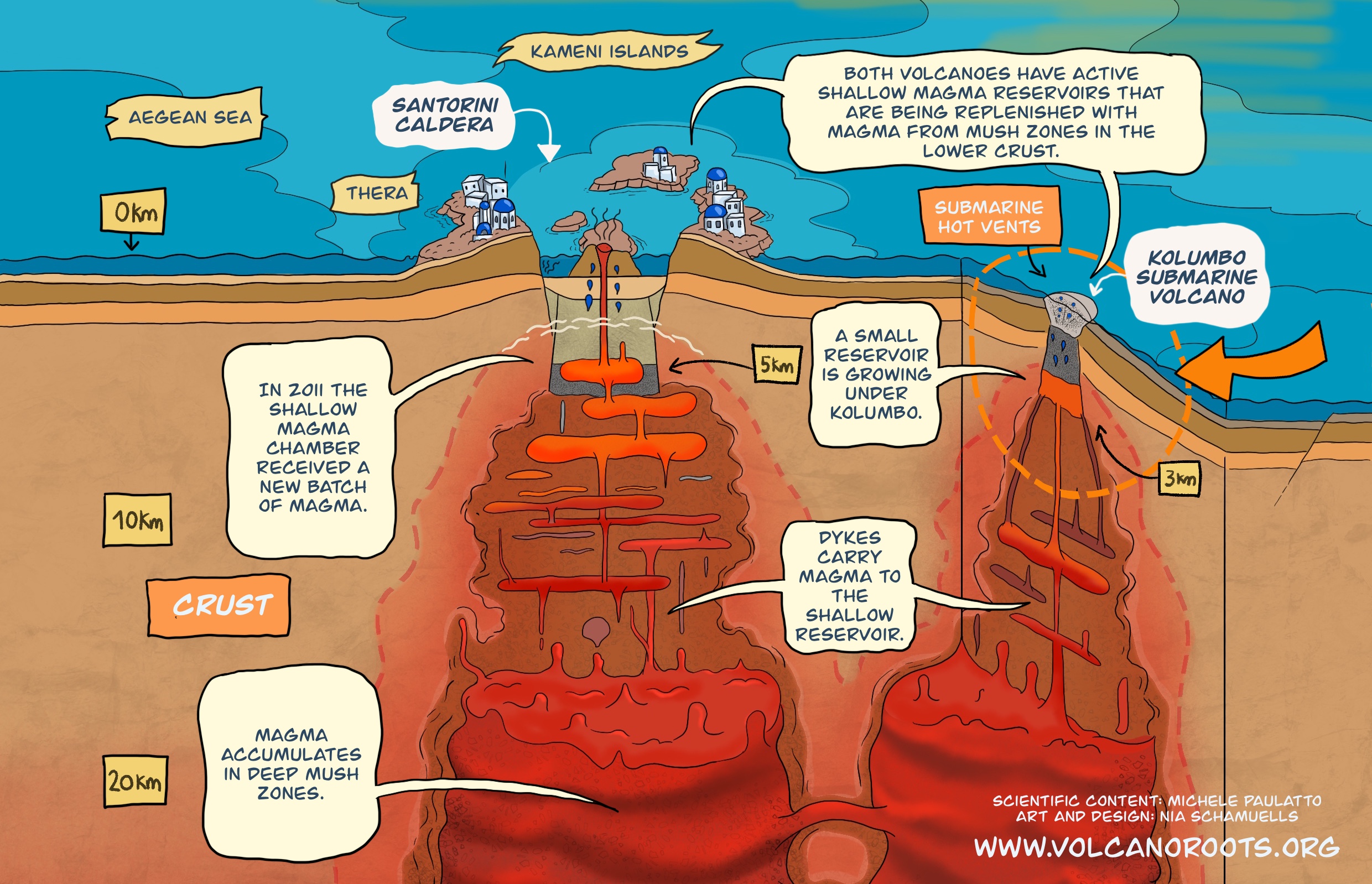

Kolumbo is located about 7 kilometres northeast of Santorini, a very popular tourist destination in the Greek archipelago of Cyclades. Santorini is not just one island but five subareal fragments of a massive caldera spanning more than 10 km in diameter, which I probably don’t need to introduce to the readers of the blog. Kolumbo’s crater is several times smaller, with its highest and lowest point at about 20 and 500 m below the sea, respectively.

Geologically, Kolumbo, along with Santorini and several other volcanoes, form the so-called Hellenic volcanic arc created by the collision of Africa and Eurasia, a process that has been going on for millions of years.

It is worth mentioning that volcanic arcs are probably the most important of several genetic types of volcanoes, not only because of their explosiveness but primarily due to their fundamental role in the process of creating new continental crust.

Curiously, these volcanoes would never have formed without enormous amounts of water that saturates the subducting tectonic plates that plunge deep into the mantle along the arcuate oceanic trenches. It is the water released at great depths from hydrous minerals making up those plates that causes the mantle to melt and subsequently give birth to magmatic plumbing systems - volcanic arcs are merely a surface expression of these vertically extensive systems. Mind you, even at this depth, the high temperature alone (i.e. without water) would not be sufficient to cause melting, neither of the mantle nor of the rapidly (in a geological sense of this word) subducting, cold, slab.

Returning to Kolumbo and Santorini, despite their proximity, these two volcanoes exhibit strikingly different behaviour. Historically, Santorini has erupted much more frequently, but it is Kolumbo that is the centre of the current hydrothermal and seismic activity. We know it since 2006, when a large field of polymetallic hydrothermal chimneys emitting gases over 200°C hot was discovered at the bottom of Kolumbo crater, sparking a flurry of studies of this previously poorly recognised volcano.

One of our findings is that the swarms of micro-earthquakes that characterise Kolumbo subsurface are very likely the “footprints” of hydrothermal fluids migrating through the rigid crust from the magma chamber towards the surface.

What is the history of Kolumbo eruptions, and what are the hazards associated with the potential awakening of this submarine volcano?

We know little about the history of Kolumbo eruptions, but it appears that there have been only a few, with an average frequency of one eruption every 200,000 years. (EDIT: most recent, still unpublished, studies suggest higher frequency). The last eruption in 1615 AD caused significant damage as a result of a tsunami. Today, we would classify the magnitude of that eruption as VEI 4-5. For comparison, last year’s Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption, the most powerful explosion recorded by scientific instruments, had a magnitude of VEI 5-6, and the famous Krakatau eruption in 1883 was VEI 6.

The current hazards are greater than they were 400 years ago. Firstly, neighbouring Santorini is besieged by tourists for most of the year with obvious consequences in an event of eruption. Apart from the direct effects of the blast and pyroclastic density currents, the ash plume and pumice rafts will disrupt air and sea transportation. What is less often known is the carbon dioxide bubble accumulated at the bottom of the crater, the release of which could lead to a phenomenon similar to the one known from Lake Nyos in Cameroon.

Why is it essential to monitor submarine volcanoes, and what challenges are posed by their monitoring?

Submarine volcanoes are exceptionally dangerous, primarily due to the threat of a tsunami. While on land various physical and chemical measurements can be employed, monitoring underwater volcanoes is much more challenging. Methods based on electromagnetic (EM) radiation, such as satellite radar interferometry used elsewhere for highly precise monitoring of vertical ground movements, are also practically impossible due to the strong absorption of EM in this frequency range by water. All instruments need to be installed underwater during costly marine expeditions. Fortunately, Kolumbo now has a subsea volcanic monitoring observatory called SANTORY, and its development can be followed at santory.gr.

What is full-waveform inversion (FWI) seismic imaging, and how is it used in the study of the Kolumbo submarine volcano?

The FWI method can be thought of as a combination of two diagnostic medical techniques - ultrasound and computed tomography (CT). As a result, we can not only precisely determine the contours of the studied object (as in ultrasound), but we can also determine its physical properties by seeing through it from different angles (as in tomography).

Unfortunately, we cannot place a volcano in a CT scanner and illuminate it with rays from every possible angle. Therefore, geophysicists had to develop much more sophisticated mathematical (e.g. inverse theory) than those used in medicine, in order to provide reliable and useful results despite less-than-perfect data. Instead of X-rays and ultrasounds, we use seismic waves generated by natural earthquakes or minor tremors generated by research equipment.

How was the presence of a magma chamber in the Greek volcano detected?

The FWI imaging method allowed us to obtain a three-dimensional model of elastic properties, specifically the seismic wave velocities, inside the volcano. These velocities are directly related to the extent to which the rock is molten. The more molten the rock, the slower seismic waves travel through it. A similar observation led e.g. to the discovery of Earth’s liquid outer core.

The connection between the rock’s physical state and the wave’s speed can be understood using the “stadium wave” analogy. A stadium (or Mexican) wave created by the audience can often be seen during big sport events, e.g. London Olympics (watch here). If spectators are tightly packed in a row, holding hands, a jump of the first person immediately “lifts” the next, and the wave propagates much faster than when they are sitting far apart. Similarly, in solid rocks, molecules are densely packed in a crystalline lattice and transmit vibrations much faster than in a liquid, even a one as viscous as magma.

Under Kolumbo, we found an area with dramatically reduced seismic wave velocities. Interestingly, this anomaly almost completely eluded the standard imaging method (applied to the data from the same experiment!) which has been the primary geophysical tool for studying volcanoes worldwide.

The velocity under Kolumbo turned out to be so low that it could not be explained solely by high temperature. In other words, some rock must exist there in a molten form. Furthermore, the degree of melting is likely high enough to refer to it as “magma”, rather than a “crystal mush” for which only very small (a few % of the rock volume) amounts of melt are distributed in microscopic spaces between crystalline grains. Interestingly, the current paradigm, contrary to the familiar textbook images depicting a large magma chamber beneath every active volcano, regards mush as the prevailing form of “existence” of melt inside the Earth, and magma chambers are considered transient, and therefore challenging to detect with geophysical methods. It is well established that magma chambers turn into mush zones by cooling down and partially crystallising if an earthquake or hot basaltic magma from greater depths do not arrive in time to trigger an eruption

How do geophysicists estimate the size/growth of a volcano’s magma chamber (using the example of Kolumbo)?

Using the effective-medium theory (also called the homogenisation theory), we can calculate the proportion of melt to solid rock from the seismic velocity of partially molten rock. Based on a three-dimensional image of the seismic wave velocity, we can estimate how much melt in total is present inside the volcano. We can also determine what proportion of melt resides as magma and how much of it is in the form of crystal mush. However, this calculation is burdened with significant uncertainty due to the fundamental ambiguity of possible geometries of rock pores in which the melt can accumulate.

Estimating the growth rate in our case is based on the assumption that all the melt was delivered/produced since the previous eruption. In other words, the previous eruption completely emptied the magma chamber. Of course, this is a huge oversimplification, and the result is subject to the greatest uncertainty among those mentioned.

In what time frame could a theoretically awakening of the Kolumbo volcano occur?

Such estimates are usually made based on the average frequency of past eruptions. For Kolumbo, we know for certain that there have been at least six eruptions in the last million years, giving an average eruption frequency slightly greater than 1 every 200,000 years. Considering that the last eruption was 400 years ago, we might feel safe. However, the inaccessibility of the deeply lying products of the past eruptions makes our understanding of the Kolumbo history quite patchy. The vigorous hydrothermal and seismic activity going on under Kolumbo calls for continuous monitoring and has led to creation of a seafloor observatory.

Currently, an expedition of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) is drilling for sediment cores in the immediate vicinity of Kolumbo. The analysis of these drilling cores will provide us with a much better understanding of the history of previous eruptions and improve our very imperfect predictions.

Photo credit: volcanoroots.org.